Color Blind

Neither steers nor fans care what color cowboy is

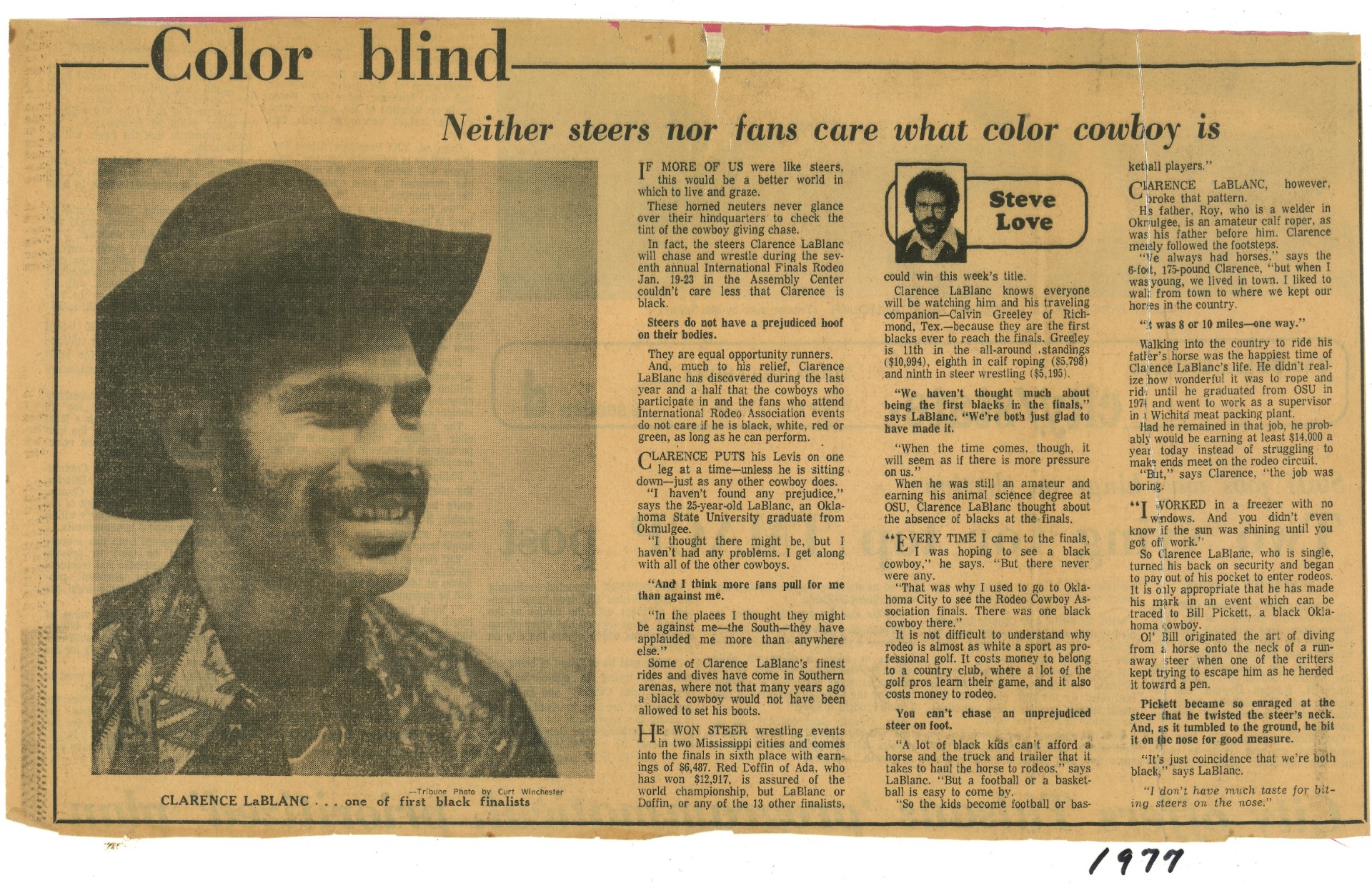

(The text from the article below was authored by Steve Love with photo by Curt Winchester, exact publisher is unknown, 1977.)

If more of us were like steers, this would be a better world in which to live and graze.

These horned neuters never glance over their hindquarters to check the tint of the cowboy giving chase.

In fact, the steers Clarence LeBlanc will chase and wrestle during the seventh annual International Finals Rodeo Jan. 19-23 in the Assembly Center couldn't care less that Clarence is black.

Steers do not have a prejudiced hoof on their bodies.

They are equal opportunity runners.

And, much to his relief, Clarence LeBlanc has discovered during the last year and a half that the cowboys who participate in and the fans who attend International Rodeo Association events do not care if he is black, white, red, or green, as long as he can perform.

Clarence puts his Levis on one leg at a time-unless he is sitting down-just as any other cowboy does.

"I haven't found any prejudice," says the 25-year-old LeBlanc, an Oklahoma State University graduate from Okmulgee.

"I thought there might be, but I haven't had any problems. I get along with all of the other cowboys.

"In the places I thought they might be against me-the South-they have applauded me more than anywhere else."

Some of Clarence LeBlanc's finest rides and dives have come in Southern arenas, where not that many years ago a black cowboy would not have been allowed to set his boots.

He won steer wrestling events in two Mississippi cities and comes into the finals in sixth places with earnings of $6,487. Red Doffin of Ada, who has won $12,917, is assured of the world championship, but LeBlanc or Doffin, or any of the 13 other finalists, could win this week's title.

Clarence LeBlanc knows everyone will be watching him and his traveling companion-Calvin Greeley of Richmond, Tex.-because they are the first blacks ever to reach the finals. Greeley is 11th in the all-around standings ($10,994), eighth in calf roping ($5,798) and ninth in steer wrestling ($5,195).

"We haven't thought much about being the first blacks in the finals," says LeBlanc. "We're both just glad to have made it.

"When the time comes, though, it will seem as if there is more pressure on us."

When he was still an amateur and earning his animal science degree at OSU, Clarence LeBlanc thought about the absence of blacks at the finals.

"Every time I came to the finals, I was hoping to see a black cowboy," he says. "But there never were any.

"That was why I used to go to Oklahoma City to see the Rodeo Cowboy Association finals. There was one black cowboy there."

It is not difficult to understand why rodeo is almost as white a sport as professional golf. It costs money to belong to a country club, where a lot of the golf pros learn their game, and it also costs money to rodeo.

You can't chase a unprejudiced steer on foot.

"A lot of black kids can't afford a horse and the truck and trailer that it takes to haul the horse to rodeos," says LeBlanc. "But a football or a basketball is easy to come by.

"So the kids become football or basketball players."

Clarence LeBlanc, however, broke that pattern.

His father, Roy, who is a welder in Okmulgee, is an amateur calf roper, as was his father before him. Clarence merely followed the footsteps.

"We always had horses," says the 6-foot, 175-pound Clarence, "but when I was young, we lived in town. I liked to walk from town to where we kept our horses in the country.

"It was 8 or 10 miles-one way."

Walking into the country to ride his father's horse was the happiest time of Clarence LeBlanc's life. He didn't realize how wonderful it was to rope and ride until he graduated from OSU in 1971 and went to work as a supervisor in a Wichita meat packing plant.

Had he remained in that job, he probably would be earning at least $14,000 a year today instead of struggling to make ends meet on the rodeo circuit.

"But," says Clarence, "the job was boring.

"I worked in a freezer with no windows. And you didn't even know if the sun was shining until you got off work."

So Clarence LeBlanc, who is single, turned his back on security and began to pay out of his pocket to enter rodeos. It is only appropriate that he has made his mark in an event which can be traced to Bill Pickett, a black Oklahoma cowboy.

Ol' Bill originated the art of diving from a horse onto the neck of a run-away steer when one of the critters kept trying to escape him as he herded it toward a pen.

Pickett became so enraged at the steer that he twisted the steer's neck. And, as it tumbled to the ground, he bit it on the nose for good measure.

"It's just a coincidence that we're both black," says LeBlanc.

"I don't have much taste for biting steers on the nose."